Multiple Early Hominins in East Africa

New fossil evidence from Ethiopia is reshaping what scientists know about human origins. Researchers say they have finally solved the mystery of the Burtele foot, first discovered more than a decade ago. The unusual set of bones — including an opposable big toe — has now been linked to Australopithecus deyiremeda, a long-debated human relative that lived at the same time as the famous Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis). The new analysis appears in a peer-reviewed scientific journal and supports the idea that early human evolution involved several closely related species rather than a single dominant lineage.

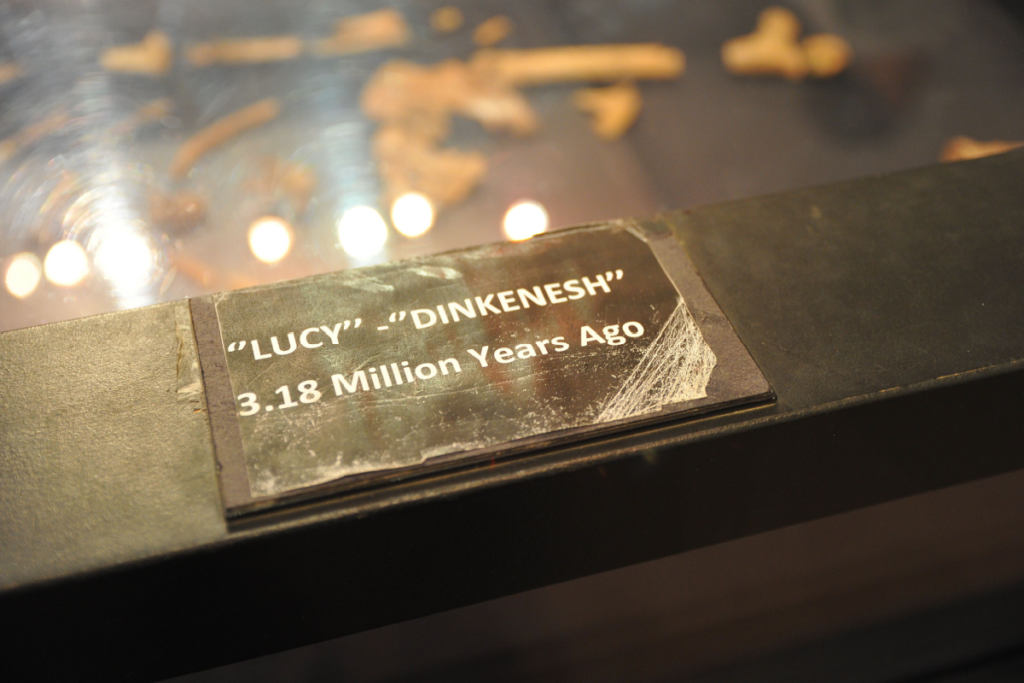

The Burtele foot was originally unearthed in sediments dating back 3.4 million years, just a short distance from the site where Lucy’s partial skeleton was found in the 1970s. At the time, experts recognized that the fossil represented a different type of early hominin because of its grasping ability, which suggested strong tree-climbing behavior alongside bipedal walking. But researchers lacked enough fossil material to propose a distinct species designation. More recent discoveries, including a juvenile jawbone with teeth, now strengthen the argument that these remains belong to A. deyiremeda.

Two Species Sharing the Same Landscape

Lucy and her species have long been depicted as the central branch in the human family tree, thought to bridge older apelike ancestors with later members of the Homo lineage. The latest findings now complicate that story. Scientists say A. afarensis and A. deyiremeda lived side by side more than 3 million years ago in what is now the Afar region of Ethiopia. This raises important questions about how two such similar hominins coexisted without competing directly for survival.

One explanation is diet and lifestyle. Chemical signatures in fossilized teeth show that A. deyiremeda relied mostly on shrubs and woody plants, while Lucy and her relatives consumed a broader range of foods, including grasses. Their feet also reveal differences in movement: the newly attributed foot fossils show that A. deyiremeda pushed off from the second toe while walking, unlike modern humans and Lucy’s species, which rely more heavily on the big toe for forward motion. These contrasts suggest that each species adapted to different ecological niches, reducing competition and allowing both to survive for long periods in the same environment.

Scientists note that this insight could shift the way early human behavior is portrayed. A single straight line of ancestry may no longer apply. Instead, the evidence supports a branching pattern — with early species experimenting with various locomotor styles and feeding strategies as they navigated changing landscapes.

Rethinking Lucy’s Place in the Family Tree

The possibility that Lucy’s species might not be the direct ancestor of modern humans is one of the most debated outcomes of the new research. For decades, Lucy has been framed as the crucial link between earlier hominins and the rise of the genus Homo. However, the closer researchers examine other species like A. deyiremeda, the more complex the evolutionary picture becomes.

Experts say the similarities between A. deyiremeda and Australopithecus africanus — a species believed to appear later in southern Africa — may indicate a different line of descent than previously thought. These findings imply several branches could have contributed to the evolutionary path toward humans. The longstanding assumption that Lucy stood alone at the root of our lineage is now being challenged.

Paleoanthropologists emphasize that more discoveries are needed before rewriting textbooks. Many of the fossils remain fragmented and difficult to interpret, and there is still uncertainty about exactly which species gave rise to later hominins. Yet even with unanswered questions, scientists agree that early human evolution is turning out to be far more diverse and dynamic than the simplified diagrams found in classrooms.

More Discoveries Ahead

Field teams plan to continue excavations across the Afar region, where both species once roamed along ancient river deltas and forested plains. Additional fossils could clarify how these early walkers interacted, adapted, and ultimately shaped the origins of our species.

For now, the Burtele foot stands as compelling evidence that Lucy was not alone — and that early human history contains more twists than previously imagined.